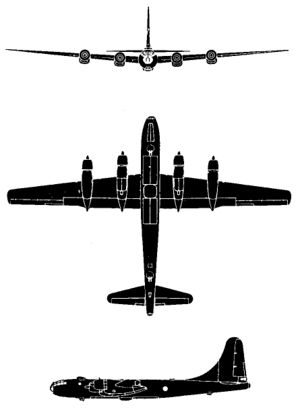

Boeing B-50 Superfortress

| B-50 Superfortress | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| First flight | 25 June 1947 |

| Introduced | 1948 |

| Retired | 1965 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 1947–1953 |

| Number built | 370 |

| Unit cost | US $1,144,296[1] |

| Developed from | B-29 Superfortress |

| Variants | Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter

Boeing KB-50 |

The Boeing B-50 Superfortress strategic bomber, was a post-World War II revision of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, fitted with more powerful Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines, stronger structure, a taller fin, and other improvements. It was the last piston-engined bomber designed by Boeing for the United States Air Force. Not as well known as its direct predecessor, the B-50 was in USAF service for nearly 20 years.

Design work began with the XB-44 Superfortress and continued when the programme was re-named B-50 in 1945. The first B-50A entered service with Strategic Air Command in June 1948 and the last bomber model (B-50D) was phased out of the active nuclear force in October 1955.

After its primary service with SAC ended, B-50 airframes were modified into aerial tankers for Tactical Air Command (KB-50) and as weather reconnaissance aircraft (WB-50) for the Air Weather Service. Both the tanker and hurricane hunter versions were retired in March 1965 due to metal fatigue and corrosion found in the wreckage of KB-50J 48-065 which crashed in October 1964.[2]

Today, no flyable B-50s remain; however several aircraft are preserved in museums for static display.

Contents |

Design and development

Development of an improved B-29 started in 1944, with the desire to replace the unreliable Wright R-3350 engines with the more powerful four-row, 28-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp-Major radial engine.[3] A B-29A-5-BN (serial number 42-93845) was modified by Pratt & Whitney as a testbed for the installation of the R-4360 in the B-29, with four 3,000 horsepower (2,240 kW) R-4630-33s replacing the 2,200 horsepower (1,640 kW) R-3350s. The modified aircraft, designated XB-44 Superfortress, first flew in May 1945.[4][5] The planned Wasp-Major powered bomber, the B-29D, was to incorporate considerable changes in addition to the engine installation tested in the B-44. The use of a new alloy of aluminium, 75-S rather than the existing 24ST, gave a wing that was both stronger and lighter, while the undercarriage was strengthened to allow the aircraft to operate at weights of up to 40,000 pounds (18,200 kilograms) greater than the B-29. A larger vertical fin and rudder (which could fold to allow the aircraft to fit into existing hangars) and enlarged flaps were provided to deal with the increased weight.[6][7][nb 1] Armament was similar to that of the B-26, with two bomb bays carrying 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of bombs, and a further 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) externally. Defensive armament was 13 × .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns (or 12 machine guns and one 20 mm cannon) in five turrets.[6][9]

An order for 200 B-29Ds was placed in July 1945, but the ending of World War II in August 1945 prompted mass cancellations of outstanding orders for military equipment, with over 5,000 B-29s cancelled in September 1945.[10] In December that year, the order for B-29Ds was cut from 200 to 60, while at the same time the designation of the aircraft was changed to B-50.[3]

Officially, the aircraft's new designation was justified by the changes incorporated into the revised aircraft, but according to Peter M. Bowers, a long-time Boeing employee and aircraft designer, and a well-known authority on Boeing aircraft, "the redesignation was an outright military ruse to win appropriations for the procurement of an airplane that by its [B29-D] designation appeared to be merely a later version of an existing model that was being canceled wholesale, with many existing examples being put into dead storage."[7]

The first production B-50A (there were no prototypes, as the aircraft's engines and new tail had already been tested) made its maiden flight on June 25, 1947, with a further 78 B-50As following.[8] The last airframe of the initial order being kept back for modification to the prototype YB-50C, a planned version to be powered by R-4360-43 turbo-compound engines. It was to have a longer fuselage, allowing the two small bomb-bays of the B-29 and the B-50A to be replaced by a single large bomb-bay, more suited to carrying large nuclear weapons. It would also have longer span wings, which required additional outrigger wheels to stabilize the aircraft on the ground. Orders for 43 B-54s, the planned production version of the YB-50C were placed in 1948, but the programme was unpopular with Curtis LeMay, commander of Strategic Air Command (SAC), as being inferior to the Convair B-36 and having little capacity for further improvement, while requiring an expensive redevelopment of air bases owing to the types undercarriage. The B-54 program was therefore cancelled in April 1949, work on the YB-50C being stopped prior to it being completed.[11][12]

While the B-54 was cancelled, production of less elaborate developments continued as a stop-gap until jet bombers like the Boeing B-47 and B-52 could enter service. Forty-five B-50Bs, fitted with lightweight fuel tanks and capable of operating at higher weights, were built, followed by 222 B-50Ds, capable of carrying underwing fuel tanks and distinguished by a one-piece plastic nose-cone.[13][14] In order to give the Superfortress the range to reach the United States chief likely enemy, the Soviet Union, B-50s were fitted to be refuelled in flight. Most (but not all) of the B-50As were fitted with the early "looped hose" refuelling system, developed by the British company Flight Refuelling Limited, in which the receiving aircraft would use a grapple to catch a line trailed by the tanker aircraft (normally a Boeing KB-29) before hauling over the fuel line to allow transfer of fuel to begin. While this system worked, it was clumsy, and Boeing designed the alternative Flying Boom method to refuel SAC's bombers, with most B-50Ds being fitted with receptacles for Flying Boom refuelling.[15][14][16]

Revisions to the B-50 (from its predecessor B-29) would result in a top speed just short of 400 mph (644 km/h), faster than many World War II propeller-powered fighters. Changes included:

- Larger engines

- Redesigned engine nacelles and engine mounts

- Enlarged vertical tail and rudder (to maintain adequate yaw control during engine-out conditions)

- Reinforced wing structure (required due to increased engine mass, larger gyroscopic forces from larger propeller, greater fuel load, and revised landing gear loading)

- Revised routing for engine gases (cooling, intake, exhaust and intercooler ducts; also oil lines)

- Upgraded fire-control equipment (to control remote turrets)

- Landing gear strengthening (takeoff weight increased from 133,500 lb/60,555 kg to 173,000 lb/78,471 kg)

- Increased fuel capacity (this was largely addressed by adding underwing fuel tanks).

- Revisions to flight control systems (the B-29 was already difficult to fly; with its increased weight the B-50 would have been much harder to hand-fly).

Redesigned with a larger upper fuselage, the B-50 design would form the basis for the Boeing 377 series of airliners and C-97/KC-97 military transports, with 816 of the KC-97 built. The B-29 and B-50s would be phased out with introduction of the jet powered B-47 Stratojet. [17]

The B-50 was nicknamed "Andy Gump" because the redesigned engine nacelles reminded aircrew of the chinless newspaper comic character popular at the time.

Operational history

Boeing built 370 of the various B-50 models and variants between 1947 and 1953, the tanker and weather reconnaissance versions remaining in service until 1965.

The first B-50As were delivered in June 1948 to the Strategic Air Command's 43d Bombardment Wing, based at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona. The 2d Bombardment Wing at Chatham AFB, Georgia also received B-50As; the 93d Bombardment Wing at Castle AFB, California and the 509th Bombardment Wing at Walker AFB, New Mexico received B-50Ds in 1949. The fifth and last SAC wing to receive B-50Ds was the 97th Bombardment Wing at Biggs AFB, Teas in December 1950. The mission of these wings was to be nuclear capable and in wartime to be able to deliver the Atomic Bomb on enemy targets if ordered by the President.[18]

The 301st Bombardment Wing at MacDill AFB, Florida received some B-50As reassigned from Davis-Monthan in early 1951, but used them for non-operational training pending the delivery of B-47A Straotjets in June 1951. It had always been intended that the B-50 would be only an interim strategic bomber, pending the availability of the B-47 Stratojet. However, delays in the Stratojet program forced the B-50 to soldier on in SAC service until well into the 1950s. [19]

A strategic reconnaissance version of the B-50B, the RB-50 was developed in 1949 to replace the aging RB-29s used by SAC in its intelligence gathering operations against the Soviet Union. There were three different configurations produced, which were later redesignated RB-50E, RB-50F, and RG-50G respectively. The RB-50E was earmarked for photographic reconnaissance and observation missions; The RB-50F resembled the RB-50E but carried the SHORAN radar navigation system designed to conduct mapping, charting, and geodetic surveys, and the mission of the RB-50G was electronic reconnaissance. These aircraft were operated primarily by the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing. RB-50Es were also operated by the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing as a replacement for RB-29 photographic reconnaissance aircraft flown over North Korea during the Korean War.[20]

The vast northern borders of the Soviet Union were wide open in many places during the early Cold War years with little defensive RADAR coverage, with limited detection capability. RB-50 aircraft of the 55th SRW flew many sorties along the periphery, and where necessary into the interior. Initially there was little opposition from the Soviet forces as radar coverage was very limited and, if the overflying aircraft were detected, the World War II era Soviet fighters could not intercept the RB-50s at their high operating altitude.[21]

The deployment of the MiG-15 interceptor in the early 1950s meant these operations became exceedingly hazardous to the crews of these aircraft, with several being shot down by Soviet air defenses and the wreckage being examined by intelligence personnel. The surviving aircrews were taken into custody and interrogated, eventually being imprisoned for years in the Soviet Gulag system until their eventual death in captivity. RB-50 missions over Soviet territory ended by 1954, being replaced by RB-47 Stratojet intelligence aircraft which could fly at even higher altitudes and at near supersonic speed.[22]

The manufacture the B-47 Stratojet in large numbers beginning in 1953 replaced the B-50Ds in SAC service; the last being retired in 1955. With its retirement from the nuclear bomber mission, large numbers of B-50 airframes were modified into aerial refueling tankers. The B-50, with it's more powerful engines than the KB-29s in use by Tactical Air Command, were much more suitable to refuel tactical jet fighter aircraft, such as the F-100 Super Sabre. KB-50s, and later KB-50Js with J-47 jet engines were used by TAC, and also by USAFE and PACAF overseas as aerial tankers. Some were deployed to Thailand and flew aerial refueling missions over the skies of Indochina in the early years of the Vietnam War until being retired in March 1965 due to metal fatigue and corrosion.[23][24]

In addition to the aerial tanker conversion, the Air Weather Service by 1955 had basically worn out the WB-29s used for hurricane hunting and other weather reconnaissance missions. Thirty-six former SAC B-50Ds were stripped of their armament and equipped for long-range weather reconnaissance missions. The WB-50 could fly higher and faster and longer than the WB-29. The WB-50 had an important role during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when it monitored the weather around Cuba to plan photo-reconnaissance flights. Although weather flying was considered a "peacetime" mission, the hazardous flying in hurricanes took their toll, and claimed 66 lives in 13 WB-50 accidents over their 10-year history in weather, also being retired in 1965 due to metal fatigue and corrosion.[25][26]

Variants

- XB-44: One B-29A was handed over to Pratt & Whitney to be used as a testbed for the installation of the new Wasp Major 28-cylinder engines in the B-29.[5]

- B-29D: Wasp Major powered bomber, with stronger structure and taller tail. Redesignated B-50A in December 1945.[3]

- B-50A: First production version of the B-50. Four R-4360-35 Wasp Major engines, 168,500 lb (76,550 kg) max take-off weight. 79 built.[27]

- TB-50A: Conversion of 11 B-50A as crew trainers for units operating the B-36.[28]

- B-50B: Improved version, with increased maximum take-off weight (170,400 lb (77,290 kg)) and new, lightweight fuel tanks. 45 built.[29]

- EB-50B Single B-50B modified as test-bed for bicycle undercarriage, later used to test "caterpillar track" landing gear.[28][30]

- RB-50B Conversion of B-50B for strategic reconnaissance, with capsule in rear fuselage carrying nine cameras in four stations, weather instruments, and extra crew. Could be fitted with two 700 US gallon (2,840 L) drop tanks under outer wings. 44 converted from B-50B.[31][32]

- YB-50C: Prototype for B-54 bomber, to have Variable Discharge Turbine (i.e. turbo-compound) version of the R-4360 engine, longer fuselage and bigger, stronger wings. One prototype started but cancelled before completion.[33][11]

- B-50D: Definitive bomber version of the B-50. Higher max take-off weight (173,000 lb (78,600 kg)). Fitted with receptacle for Flying boom in-flight refuelling and provision for underwing drop tanks. Modified nose glazing with 7-piece nose cone window was replaced by a single plastic cone and a flat bomb-aimer's window. 222 built.[34][35]

- DB-50D: Single B-50D converted as drone director conversion of a B-50D, for trials with the GAM-63 RASCAL missile.[36][35]

- KB-50D: Prototype conversion of two B-50Ds as three-point air-to-air refuelling tanker, using drogue-type hoses. Used as the basis for later production KB-50J and KB-50K conversions.[37][38]

- TB-50D: Conversion of early B-50Ds lacking air-refuelling receptacles as unarmed crew trainers. Eleven converted.[39][38]

- WB-50D: Conversion of surplus B-50Ds as weather reconnaissance aircraft to replace worn out WB-29s. Fitted with doppler radar, atmospheric sampler and other specialist equipment, and extra fuel in the bomb-bay. Some were used to carry out highly classified missions for atmospheric sampling between 1953 and 1955 to detect Soviet detonation of atomic weapons.[40][41][42]

- RB-50E: 14 RB-50Bs converted at Wichita for specialist photographic reconnaissance.[43][44]

- RB-50F: Conversion of 14 RB-50Bs as survey aircraft, fitted with SHORAN navigation radar.[45][46]

- RB-50G: Conversion of the RB-50B for electronic reconnaissance. Fitted with Shoran for navigation, and six electronic stations, with 16-man crew. 15 converted.[46][41]

- TB-50H: Unarmed crew trainer for B-47 squadrons. Twenty four completed, the last B-50s built. All later converted to KB-50K tankers.[47]

- KB-50J--Conversions to air to air refueling tankers with improved performance, via two extra General Electric J47 turbojets under the outer wings, 112 converted.

- KB-50K--Tanker conversions of the TB-50H trainer aircraft. 24 converted.

- B-54A--Proposed version of the YB-50C.

- RB-54A--Proposed reconnaissance version of the YB-50C.

Survivors

Only five B-50 type aircraft survive today, from the 370 produced:

- B-50A-5-BO, AF Serial No. 46-0010. This aircraft, Lucky Lady II, is disassembled and the fuselage is stored outside at The Air Museum Planes Of Fame in Chino, CA.

- WB-50D-115-BO, AF Serial No. 49-0310. This aircraft has been moved indoors to the Cold War Gallery after many years (since 1966) being on static display outside at the National Museum of the USAF in Dayton, OH.

- WB-50D-120-BO, AF Serial No. 49-0351. This aircraft is displayed outdoors at Castle Air Museum in Atwater, CA. This was the last B-50 which was flown, being delivered to MASDC on 6 October 1965. It was put on display at the Castle AFB museum in 1980.

- KB-50J AF Serial No. 49-0372. This aircraft is displayed outdoors at Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, AZ.

- KB-50J AF Serial No. 49-0389. This aircraft is displayed outdoors at McDill AFB in Tampa, FL (Not accessible to the public)

Operators

- B-50 Superfortress

- 2d Bombardment Wing, 1949-1953

- 43d Bombardment Wing, 1948-1954

- 93d Bombardment Wing, 1949-1954

- 97th Bombardment Wing, 1950-1955

- 306th Bombardment Wing, 1951

- 509th Bombardment Wing, 1949-1951

- RB-50 Superfortress

- 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, 1950-1954

- 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, 1949-1950 (B-50); 1950-1951

Tactical Air Command[49]

- KB-50 Superfortress

- 420th Air Refueling Squadron, 1955-1964 (USAFE)

- 421st Air Refueling Squadron, 1955-1965 (PACAF)

- 427th Air Refueling Squadron, 1959-1963

- 429th Air Refueling Squadron, 1958-1963

- 431st Air Refueling Squadron, 1957-1965

- 622d Air Refueling Squadron, 1957-1963

- WB-50 Superfortress

- 53d Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1955-1965

- 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1955-1960; 1962-1965

- 55th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1958-1960 (TB-50); 1960-1963

- 56th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1956-1962

- 57th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1956-1958

- 58th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1956-1958

- 59th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, 1955-1960

Specifications (B-50D)

Data from Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973[52]

General characteristics

- Crew: 8: Pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer, radio/electronic countermeasures operator, two side gunners, top gunner and tail gunner

- Length: 99 ft 0 in (30.2 m)

- Wingspan: 141 ft 3 in (43.1 m)

- Height: 32 ft 8 in (10.0 m)

- Wing area: 1720 ft² (159.9 m²)

- Empty weight: 84,714 lb (38,506 kg)

- Loaded weight: 121,850 lb (55,270 kg) (combat weight)

- Max takeoff weight: 173,000 lb (78,470 kg) (max overload weight)

- Powerplant: 4× Pratt & Whitney R-4360-35 radial engines, 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 394 mph (343 knots, 635 kph) at 30,000 ft (9,150 m)

- Cruise speed: 244 mph (212 knots, 393 km/h)

- Combat radius: 2,394 mi (2,082 nmi, 3,855 km)

- Ferry range: 7,750 mi[34] (6,739 nmi,12,478 km)

- Service ceiling: 36,900 ft (11,250 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,200 ft/min (11.2 m/s)

- Wing loading: 70.19 lb/ft² (343 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.115 hp/lb (193 W/kg)

Armament

- Guns:

- 13× .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns in 4 × remote controlled and manned tail turret

- Bombs:

- 20,000 lb (9,100 kg) internally

- 8,000 lb (3,600 kg) on external hardpoints

See also

Related development

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress

- Boeing 377 Stratocruiser

- Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter

- Boeing XB-44 Superfortress

- Tupolev Tu-4

Related lists

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

- Footnotes

- Notes

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 174.

- ↑ Serial Number Search, B-50 48-065

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Knaack 1988, p. 163.

- ↑ Bowers 1989, p. 336.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Boeing/Pratt & Whitney XB-44 factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 27 June 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Peacock 1990, p. 204.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bowers 1989, p. 345.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bowers 1989, p. 346.

- ↑ Bowers 1989, p. 347.

- ↑ Bowers 1989, p. 325.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Knaack 1988, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Willis 2007, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Willis 2007, p. 162.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Peacock 1990, pp.205–206.

- ↑ Willis 2007, pp. 156–158.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ B-50 phase out for B-47

- ↑ Ravenstein, Charles A. Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories, 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1984. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- ↑ Ravenstein, Charles A. Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories, 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1984. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- ↑ Baugher - Boeing B-50B Superfortress

- ↑ Spyflight.com - Boeing F-13A / RB-29A / RB-50

- ↑ Spyflight.com - Boeing F-13A / RB-29A / RB-50

- ↑ Tac Tankers.Com

- ↑ Baugher - Boeing KB-50 Superfortress

- ↑ Hunters Association

- ↑ Baugher, Boeing WB-50D Superfortress

- ↑ "Boeing B-50A Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Peacock 1990, p. 205.

- ↑ "B50B Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Favonius." "American Notebook: Some Caterpillars Fly." Flight, 7 July 1949, p. 24.

- ↑ "RB-50B Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p.177.

- ↑ "YB-50C Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "B-50D Factsheet". National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 28 June 2010.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Bowers 1989, p. 348.

- ↑ "DB-50D Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 30 June 2010.

- ↑ "KB-50D Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 30 June 2010.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Peacock 1990, p. 206.

- ↑ "TB-50D Factsheet". National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ "Boeing WB-50D Superfortress." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 30 June 2010.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Peacock 1990, p. 207.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ "Boeing RB-50E." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 30 June 2010.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ RB-50F Factsheet." National Museum of the US Air Force. Retrieved: 30 June 2010.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Knaack 1988, p. 179.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, pp. 197–199.

- ↑ Ravenstein, Charles A. Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories, 1947–1977. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1984. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- ↑ TAC Tankers.Com

- ↑ [Mauer, Mauer (1969), Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II, Air Force Historical Studies Office, Maxwell AFB, Alabama. ISBN: 0892010975

- ↑ Air Force Weather Reconnaissance Organizational History

- ↑ Knaack 1988, pp. 200–201.

- Bibliography

- Bowers, Peter M. Boeing Aircraft since 1916. London: Putnam, 1989. ISBN 0-85177-804-6.

- Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey. Flight: 100 Years of Aviation. Harlow, Essex, UK: DK Adult, 2007. ISBN 978-0756619022.

- Jones, Lloyd S. U.S. Bombers, B-1 1928 to B-1 1980s. Fallbrook, CA: Aero Publishers, 1962, second edition 1974. ISBN 0-8168-9126-5.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1988. ISBN 0-16-002260-6.

- Peacock, Lindsay. "The Super Superfort". Air International, Vol. 38, No 4, April 1990, pp. 204–208. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Willis, David. "Warplane Classic:Boeing B-29 and B-50 Superfortress". International Air Power Review. Volume 22, 2007. Westport, Connecticut:AIRtime Publishing. ISBN 188058879X. ISSN 1473-9917. pp. 136–169.

External links

- B-50 Design and Specifications, Global Security.org

- Boeing B-50 Superfortress, Joe Baugher

- B-29 & B-50 production batches and serial numbers

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||